So declared a celebratory public illumination in Dublin city 10 days after the battle of Waterloo had been fought. It might seem astonishing now to hear that the news of Wellington’s victory over Napoleon took 3 days and 2 hours to reach the London press, 1 but it took even longer to reach Ireland. Eight days after Wellington had routed the French army, the general’s dispatch was finally reproduced in full in the Irish papers. 2

Alongside the relief and joy found across Britain, the Irish papers were additionally pleased because Wellington was an Irishman. To the Freeman’s Journal, he was ‘our truly great and gallant-minded countryman’. 3 Wellington himself did not build a career on his Irishness, preferring the British army to Irish politics. It was Daniel O’Connell who famously said ‘He was born in Ireland; but being born in a stable does not make a man a horse.’ 4 Naturally, Wellington’s conspicuous absence of Irish patriotism did not dampen the ardour of the Irish public. The Dublin Journal took his victory as further proof that ‘the men of Ireland are instinctively brave – that courage is indigenous to the soil’. Unfortunately, Wellington was rarely in Ireland, since he did not even own an estate in the country. His Irishness was definitely compromised by this so the writer suggested that the Crown grant ‘our Wellington’ the Curragh of Kildare for his own. 5 In this completely over-the-top suggestion, the writer reveals how desperate some were to appropriate Wellington for the Irish nation. The Irishmen who fought and died as ordinary soldiers merited no mention at all.

To celebrate the victory, the population of Dublin enjoyed public illuminations, where lamps were hung in an artistic manner on public buildings or shopfronts. Vivid tableaux were created by placing lamps behind transparencies, illuminating dramatic scenes, mottoes and symbols. College Green in Dublin was transformed by these displays on 28 June. Trinity College, the Post Office and the Bank of Ireland presented a dazzling vision to admiring spectators. The College had the most elaborate display, with a 60 foot (18m) crown surrounded by the King’s arms, a bust of the Prince Regent and the motto ‘British Firmness, the source of Europe’s deliverance’. A ghostly hand holding a scimitar emerged from clouds to break the chains around Europe, with the names of the great generals ‘Wellington’ and ‘Blucher’ in scrolls all around. It all looked ‘magnificently grand’.

In Mr Kertland’s business premises (in 1805 he ran a ‘Fancy Ware-House’) was an illumination of ‘peculiar taste’. A transparency showed the female figures of Justice, Virtue and Humanity ‘darting their spears into the breast of Bonaparte, who with broken swords reeking with blood, is falling among fiends and furies’. This gripping scene excited much admiration. In an adjoining window, a wreath of roses, shamrock and thistle encircled the words ‘Peace to the World! Plenty to the Poor!’. 6 The apocalyptic hyperbole captures the profound relief of a public that had been terrified of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Unfortunately, the victory at Waterloo did not lead to an improvement in daily life in Ireland. Demobilised ex-soldiers and sailors, many with disabling injuries, flooded the labour market just as the government stopped purchasing large amounts of provisions for the armed forces. In Ireland, factories producing linen for the military market laid off workers and prices for agricultural goods dropped steadily. As there was no Poor Law system until 1838, the poorest had to turn to their neighbours, their churches and local charities for support. International peace did not mean full bellies or warm fires for ordinary people.

The grim post-war economic situation did not dim the appreciation of public bodies for the heroic leaders of the victorious British army. Urban areas granted freedom of the city to Waterloo veterans, offering them membership of exclusive city governing bodies. Twenty-six men who had fought at Waterloo were made freemen of Cork city. 7 Even a famous Irish casualty of the battle, Sir William Ponsonby, was posthumously made a freeman. But most illustrious of all, the city of Cork granted its freedom to Field Marshall Blücher of the Prussian army, the man whose forces fortified Wellington’s at a crucial moment.

Like a contemporary politician collecting honorary doctorates, Blücher must have received many civic and national honours after Waterloo. However, the Corporation of Cork did not send him notification of his freedom in the ornate gold box that etiquette dictated. The city worthies might have felt that a costly gift to a German noble with no knowledge of the city would be an expensive waste of time. Other institutions were not so parsimonious when bestowing honours on Waterloo veterans. The Earl of Uxbridge, who commanded the heavy cavalry at Waterloo, had become famous for his reaction to a cannonball in the leg. He exclaimed to the nearby Wellington ‘By God, sir, I’ve lost my leg!’, to which the Duke replied ‘By God, sir, so you have!’. (His amputated leg later became a tourist attraction in Waterloo.) When appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1828, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Trinity College Dublin, receiving a heavily decorated gold box to mark the occasion.

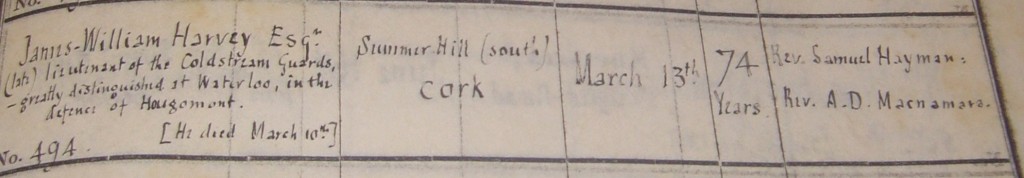

Any officer who had fought at Waterloo was judged to have achieved something truly remarkable. There were thousands of men on the battlefield but of those who survived, it was the officers who became famous. John Booth’s multi-edition account of the battle listed ‘the names of the officers employed with their respective ranks and several casualties’ while ordinary soldiers remained anonymous. Being on the battlefield ensured perpetual fame: when James-William Harvey was buried in Cork in 1873, that he was ‘greatly distinguished at Waterloo’ was carefully noted in the burial register. This was an extraordinary note in a register that gives no additional details on anyone else, even local grandees. It is testament to the enduring significance of Waterloo in the public memory.

Of course, like urban areas all over Britain, Ireland has its fair share of placenames inspired by the famous victory. Cork has a Wellington Road, Place, Bridge, Avenue, Terrace and Square while Dublin boasts Wellington Road, Quay, Place, Street, Bridge and a colossal monument in the Phoenix Park, erected in 1861.

This obelisk, with four bronze plaques cast from cannons captured at Waterloo, was completed 9 years after the Duke’s death, proving the enduring interest of Dublin in Wellington. 8 The battle of Waterloo, led by the most famous Irishman of his era, was remembered in Ireland for decades afterwards.

But public narratives of history change and Irish people are now more ambivalent about the Irishness of the Duke of Wellington. Finally, the lives of ordinary soldiers are to forefront of the popular imagination. Men of humble origins who signed up and fought against Napoleon are described in this TG4 programme with as much zeal as previous generations expended on the officers. The women who followed these men to the battlefield are also part of the story of Waterloo. While Wellington continues to dominate the story of Waterloo, smaller characters in the great historical drama are at last accorded a little space.

- Brian Cathcart, The News from Waterloo: the Race to tell Britain of Wellington’s Victory (2015). ↩

- The dispatch was carried by both the Belfast Newsletter and the Freeman’s Journal on 26 June 1815. ↩

- Freeman’s Journal, 29 June 1815. ↩

- http://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/a-bit-of-welly-the-iron-duke-s-irishness-1.1546456. See also http://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/the-duke-of-wellington-s-drunken-dublin-years-1.2244707 for why Wellington did not say these words ↩

- Excerpted in the Freeman’s Journal, 30 June 1815. ↩

- Freeman’s Journal, 29 June 1815. ↩

- http://www.corkarchives.ie/media/freemen1710-1841.pdf ↩

- http://archiseek.com/2010/1861-wellington-monument-phoenix-park-dublin/ ↩