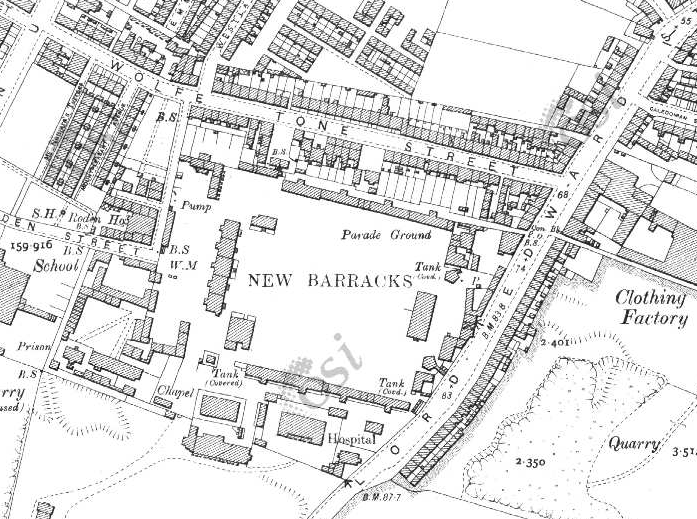

In May 1888, the War Office sent a representative to Limerick city to investigate fisticuffs, riotous assemblies and stone-throwing between soldiers and civilians that threatened the future of Limerick as a garrison town. Since the beginning of April, members of the Derbyshire (Sherwood Foresters) regiment had been beaten, stoned and robbed of their belts and caps by ‘rougher’ elements of Limerick society. Incensed soldiers broke out of the New Barracks twice, roaming the streets looking for a fight until the police and a military picket returned them their quarters. 1 Colonel Henry Hodson Hooke informed the Mayor that he would switch the barrack provisioning contracts from Limerick to London if his soldiers could not walk the streets safely. 2 The city’s elites worried about losing £35,000 worth of military business but this threat to commerce did not quell troublesome ‘roughs’. 3 Conflict between military and civilians was not unusual in garrison towns but it was exceptional for police to contain six street mobs (4 civilian, 2 military) in one month. Why were relations between Limerick people and the Derbyshire Regiment so strained? The 5th Hussars and the Artillery stationed in the city did not attract the same public opprobrium in 1888.

https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1970-12-200-3

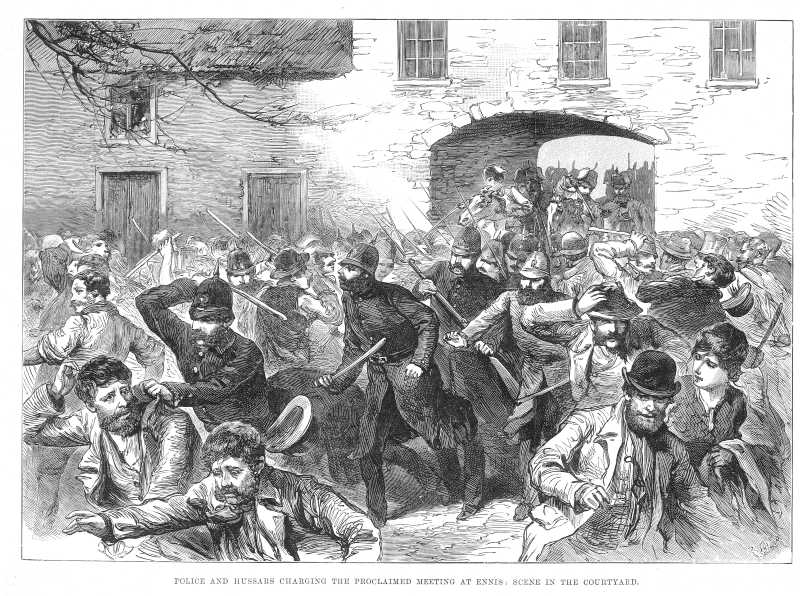

The Derbyshires were unfortunately addicted to singing ‘Rule Britannia’ in the course of their duties. When the regiment policed the funeral in March of Stephen Joseph Meany, a Clare Fenian, they offended the large, peaceable crowd by singing ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘God Save the Queen’ as they marched. 4 Journalists believed this was the reason for an outbreak of violence two weeks later, when soldiers were beaten and stoned in Limerick city. Fifty soldiers, brandishing their belts as weapons, ran down Colooney street looking for trouble until a military picquet returned them their quarters. 5 However, officers did not change their regimental habits and the Derbyshires sang lustily during their police work in Ennis, where their voices interrupted Catholic mass. Alongside the 5th Hussars and the police, the infantry were accused of using excessive force to suppress a proclaimed meeting of the Land League. 6

http://www.mayolibrary.ie/media/Newspaper_illustrations/Webpages/detail.np/detail-54.html

Thirteen days after the Ennis controversy Limerick civilians expressed their antipathy towards the Derbyshires in mob violence. From 22 April to 7 May, four civilian mobs chased, stoned and beat soldiers. In the first serious incident, 16 soldiers were chased on Glenworth Street by a stone-throwing mob that quickly dispersed at the sight of the police. 7 The hard-working constabulary intervened again on 29 April, when soldiers broke out of the New Barracks twice ‘jostling and calling names to the people on the streets’. According to some accounts, they sang ‘Rule Britannia’, adding ‘Up with England’ and ‘Down with Ireland’ for good measure. 8 A large crowd in Colooney Street threw stones and sticks at the military men while the police kept the both sides apart. Military discipline had evaporated, forcing the police to guard all the barrack exits to keep the soldiers inside the walls. 9

Another ‘riotous assembly’ of angry civilians stoned soldiers on Barrington Street the following night. 10 Smaller scuffles occurred in other parts of the city that evening, proving the fractiousness of the military-civilian relationship. The Derbyshires could not walk the streets of Limerick unmolested: on 7 May a group of five were followed by a crowd of women and children ‘groaning and hooting’. The soldiers were accused of provoking assaults by saying ‘Bloody Irish Papists’. 11 Harassed policemen spent much of April and the beginning of May separating soldiers and civilians, escorting military men through the streets and sheltering them in constabulary barracks until calm was restored. Civilians were so irked by the Derbyshires that they threw stones over the barrack walls. 12 Magistrates handed out prison sentences to almost all those accused of assaulting soldiers but the violence continued until the War Office representative visited the city.

http://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/view/edition/2290

There is no indication that Colonel Hooke spoke to his soldiers about their behavior during these quarrelsome weeks. Yet after the War Office visit, Hooke addressed the regiment on parade, warning that ‘any provocation’ of civilians would be severely punished. His other order – an end to ‘singing around the barrack square’ – was perhaps more important.13 The Derbyshires sang as they marched within the barracks, probably practicing their favourite tune ‘Rule Britannia’. Limerick people couldn’t ignore this ‘party’ song when the regiment sang in the open air of New Barracks square. Provoked almost daily by a song they found deeply offensive, civilians threw stones over the walls and at soldiers on the streets. After the martial singing ceased, the street battles ended. The regiment’s musical choices explain both the persistence of the violence and its cessation in mid May. The War Office rarely intervened in routine regimental affairs but it is no coincidence that Hooke’s decision occurred after a London representative visited. The regiment did not abandon it’s favourite song, marching to ‘Rule Britannia’ even when policing contentious evictions. 14 Occasionally, ‘young lads’ threw stones at Derbyshire men as they walked the streets but clashes between mobs and roving bands of soldiers were at an end. 15 Limerick city tolerated the Derbyshire Regiment once the commanding officer abandoned a music policy that needlessly offended popular nationalist sentiment.

- Cork Constitution, 4/4/1888, Cork Examiner, 1/5/1888. ↩

- Cork Examiner, 7/4/1888 ↩

- Cork Examiner, 12/5/1888. ↩

- Cork Constitution, 4/4/1888, People’s Advocate, 17/3/1888. ↩

- Cork Constitution, 4/4/1888; Kerry Weekly Reporter, 7/4/1888 ↩

- Loughlin Sweeney, Irish Military Elites, Nation and Empire, 1870-1925 Identity and Authority (2019) pp 111-113. ↩

- Cork Examiner, 5/5/1888. ↩

- Cork Examiner, 1/5/1888; Cork Constitution, 1/5/1888. ↩

- Freeman’s Journal, 1/5/1888. ↩

- Cork Examiner, 7/5/1888 ↩

- Cork Examiner, 8/5/1888, 12/5/1888. ↩

- Cork Examiner, 21/4/1888. ↩

- Cork Examiner, 14/5/1888. ↩

- Cork Examiner, 27/7/1888. ↩

- Cork Examiner, 2/6/1888, 22/9/1888. ↩