A guest post from David Toms about the ‘garrison game’….

‘Support your own games. Don’t mind the skulker and miserable kind of fellow who says, “There’s no game like Soccer”, “No game like Rugby”- in fact, “No game like the game that is my own”. Be men. The skulking slave spirit has got into our people – that is the reason for slavishly following foreign games and customs. Let us be strongly national – that is not bigotry.’ 1

‘There is grave danger of a big land-slide towards West Britonism as exemplified by the Jazz-Soccer-Golfstick mentality which is on the increase in this country today.’ 2

The above quotes, taken from local newspapers, are indicative of the attitudes that began to emerge in Ireland regarding just about any ‘foreign’ influence aimed not just at games like soccer, but also increasingly at new, emerging music such as jazz. In the 1920s, when Ireland became independent, Irish people were encouraged by their government and the media to buy Irish goods, eat Irish food, drink Irish beer and be buried in Irish clothes. They were also encouraged to dance to Irish music and play Irish games. Anyone who didn’t engage in these activities was labelled a ‘West Brit’ or a ‘shoneen’, two terms that suggested that someone was pro-British and anti-Irish in their attitudes, tastes, and politics. One sport which confounded these expectations of Irishness in the newly independent state was soccer. But where did this link between association football and the British military, specifically the army, actually come from? How much of it was simple cultural chauvinism, and how much truth was there behind the charge of association football as the garrison game?

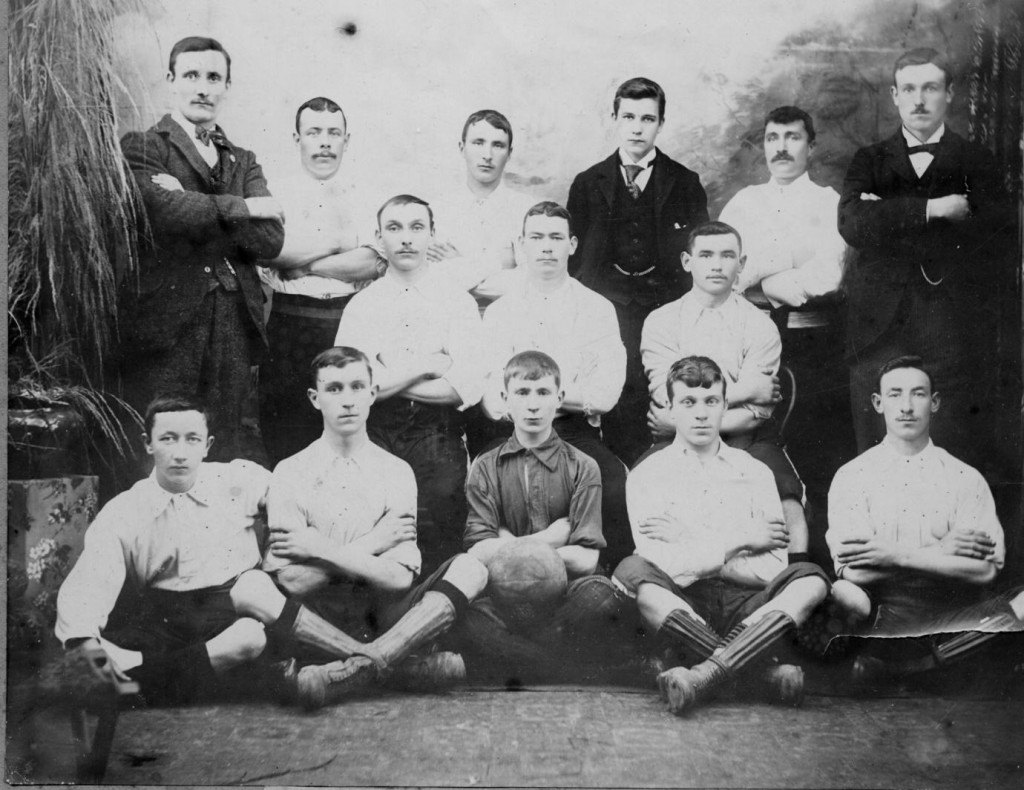

Soccer was played in Ireland since the late 1870s in Belfast, Dublin and Donegal but also in Westmeath and Cork. The Irish Football Association was founded 1880, the Leinster Football Association in 1892 and the Munster Football Association in 1901. Throughout this early period of the game’s development, both the military and civilians were fundamental agents of its spread. While there was no shortage of military teams emerging from the garrisons of Munster, there was equally no shortage of civilian teams to be found throughout the province. Just a sample of such teams from Cork included: Berwick, Hibernians, Celtic Strollers, Barrackton United, Cathedral Rovers, and many more were all playing in the city and environs from the early 1900s to the beginning of the First World War.

In Waterford in the pre-First World War period, among the teams playing were Gracedieu Emmets, Urbs Intacta (from the city’s motto urbs intacta manet), De La Salle, Barrack Street Ramblers, and Tramore Celtic. You’ll notice perhaps the names of Barrackton in Cork and Barrack Street Ramblers in Waterford and certainly these do indicate proximity to barracks, but the young men who played in these sides were local civilians. You’ll notice too that many of the other clubs have Irish names like Celtic, Emmets, or names that denote little more than the areas they are from, or their schools. There is a mixture of Catholics and Church of Ireland to be found amongst these different micro-social networks.

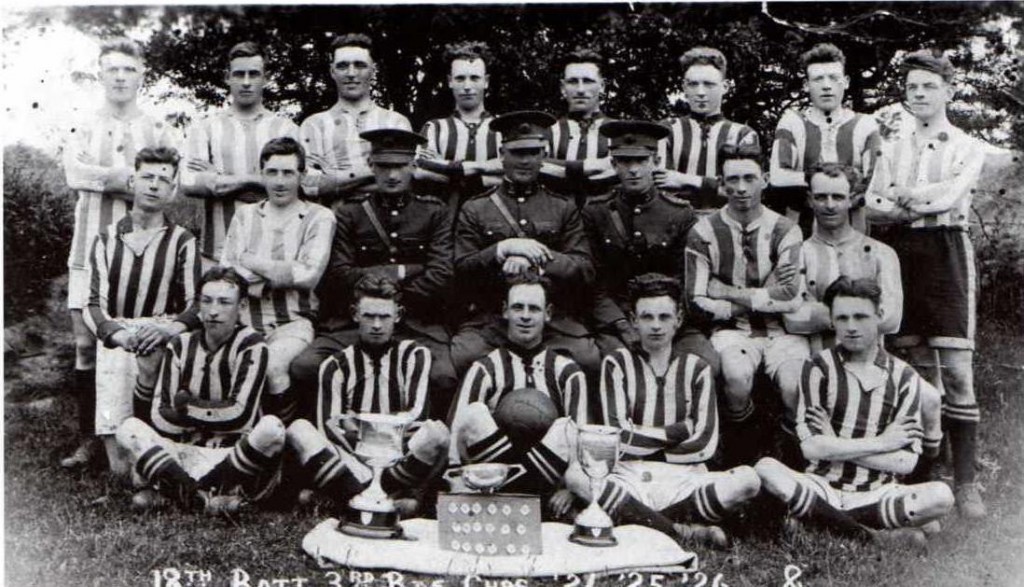

In the two other places to see soccer emerge in Munster at the time, Tipperary and Limerick, the military influence certainly does appear to be more noticeable. For the civilian clubs that emerged in the various places in Tipperary like Cahir and Clonmel especially, the military connections were strong. One of the major patrons of Cahir Park FC was Colonel Richard Butler Charteris, and a good number of Cahir Park FC players died in the First World War, their names remembered on a championship cup still contested today.

These military connections would see the club listed by South Tipperary No. 3 Brigade of the IRA as one of the enemy institutions in the area in 1921. 3 Interestingly, one of the players for Cahir Park, James McNamara, who played soccer before the First World War was also a senior All-Ireland medal winner with Tipperary in 1920, playing in the famous “Bloody Sunday” match in Croke Park – so it was possible to play both garrison and Gaelic games. In Limerick, one of the early important civilian sides, Limerick AFC, founded in 1908, certainly relied on local military sides to provide them with opponents. Yet, their efforts paid off as a promoter of the game: by 1912, more civilian soccer teams began to emerge in the city. In Munster, the growth of soccer reveals a complex relationship between the military and civilian teams.

One area where military dominance was obvious was in the committee of the local governing body of the sport, the Munster Football Association, which had been founded in 1901. But the strong military presence on that committee was in fact resented and often a negative for the game’s development among the civilian population. The official control of the game by the military meant that soccer was played on Saturday afternoons, usually between three and four p.m, when many civilians were still at work. In the round up of the 1908/1909 season, “Centre Forward” had noted that, ‘A great obstacle to the games in Cork being attended is the lack of a general half-holiday, and I venture to predict that when that drawback is eliminated the attendance at local Soccer matches will far exceed that of past seasons.’

It was noted in the soccer column of “Centre-Half” that because the Saturday half-holiday wasn’t universal it meant that many of the civilian teams in Cork could not put out full sides on a Saturday afternoon as many were ‘perhaps, out of town or detained at business.’ The same issue was noted again in 1909 and 1910 when it was acknowledged that ‘with the near approach to Xmas [sic] the local civilian clubs find it difficult to field representative elevens. Many of their prominent players being engaged up to a late hour on Saturdays.’ 4 Given that the city had witnessed a major lockout in 1909 of workers who had attempted to organise themselves into unions, those with work were no doubt keen to hold on to it.

With so many players and organisers in the military, winter-time furlough (a break for soldiers for the months of December and January) also played a significant role in the shape of the season and was the root cause of the cluttered pre-Christmas calendar of fixtures. So, in some years football could halt for close on two months, taking much of the steam out of the leagues and competitions, particularly for the civilian sides. All of this led to supreme dissatisfaction amongst civilian clubs, many of whom simply opted out of the Munster FA’s structures and organised games in their own time. But like everywhere else in Ireland, the First World War would slow the progress of the game among civilians.

After 1922, soccer, controlled in the new 26-county state by the Football Association of the Irish Free State (FAIFS), emerged as one of the most popular sports of the interwar period in Ireland. Based in Dublin, the new FAIFS watched as the game grew and spread around the country, with teams including Fordson FC based in the Ford factory in Cork, Waterford FC and Limerick FC joining more well-known Dublin sides like Bohemians, Shelbourne, St. James Gate and Jacob’s in the new Free State League. Cork saw the re-founding of the Munster FA in 1922. A new Waterford and District Football League was formed in 1924 and the Limerick District Football Association was formed in the same year.

That this happened after the garrisons had seen their personnel change from British soldiers to Free State soldiers, suggests that the greater legacy, with a longer lasting impact, of the pre-First World War soccer players was not those who manned the garrisons in their towns, but those who played in the streets and fields around them, under their street names. The so-called ‘garrison game’ was strongest once the British garrison that had introduced it was gone.

David Toms is an occasional lecturer and former tutor in the School of History at University College Cork. His book, Soccer in Munster: A Social History, 1877-1937, is forthcoming in May from Cork University Press. He blogs regularly for The Dustbin of History and on his own blog. He tweets as @daithitoms

- Nenagh Guardian, January 14 1928. ↩

- Nenagh Guardian, July 14 1928. ↩

- Military Archives, Dublin, A/0745 South Tipperary Brigade No. 3 Brigade Report, November 1921; Other institutions listed as enemies in the same document included the golf clubs of Tipperary, Clonmel, and Cahir. On McNamara see Paul Buckley, Cameos of a Century, (Cahir, 2010), p 9. ↩

- Cork Sportsman, October 17 1908; May 22 1909; December 17 1910. ↩