Cross-posted from How to be the hero of your own kitchen

Thanks to Rocio C. for asking me to combine two of my life’s obsessions: food and research!

Recruiting sergeants, while plying potential soldiers with drink, waxed lyrical about the comforts of army life. Regular, daily meals and a bed to himself would have seemed luxurious to many men who joined the army, because most recruits were among the poorest in society. But the quality and quantity of food served to the British soldier during the nineteenth century was poor and inadequate. Even worse, the unlucky recruit soon discovered that he had to pay for that food out of his meagre daily wage of 1 shilling as part of a ‘stoppages’ system, whereby soldiers paid for their own clothing, boots, food and equipment. 1 While the Treasury and War Office slowly, reluctantly improved soldier’s living conditions, it wasn’t until the complete collapse of the provisioning system during the Crimean War that public attention was focused on the soldier’s diet and accommodation.

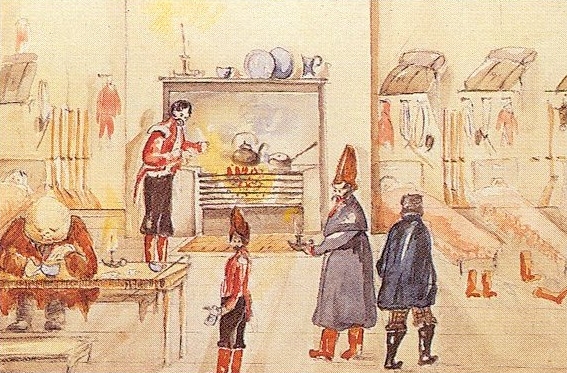

Until 1844, a soldier was served just 2 meals a day: breakfast and dinner. The 1 pound (450g) bread ration was served in the morning accompanied by tea or coffee. If a man did not eat this hunk of bread immediately, he had no place to store it so it was invariably stale within hours. This illustration of the barrack room shows the room where men ate, slept and relaxed. It was not a room designed with food storage in mind, although some rudimentary cooking was possible on the open fire.

At midday, the only hot meal of the day was distributed. Each man was allocated three-quarters of a pound (340g) of raw beef or mutton a day but when it had been boiled and deboned, it probably only weighed half that. The meat was always boiled because there were no other cooking facilities available and it was served in a broth that had been thickened with potatoes, peas or flour. Any other vegetables had to be bought by the men themselves and, luxuries like sugar and fresh milk were purchased by the men as a group, from levies made on their pay. Soldier’s families were given half rations but only if the marriage had been permitted by the commanding officer. Service families ‘on the strength’ lived in the barrack rooms until married quarters became common in the late nineteenth century, but regulations permitted just 6% of men to marry. 2 Many soldiers married without permission, and those families ‘off the strength’ received no food, save what rations men could share.

All across Britain and the Empire, from Bandon to the Bahamas, the British soldier ate the same food. Foreign stations imported their meat from Britain, salted and packed in barrels to survive the long journey. In the heat of the tropics, a diet of salted meat and dry bread created a raging thirst among men who had little to drink but spirits. 3 Soldiers abroad were supplied by the Board of Ordnance, whose inadequate supervision of food quality drew complaints. Bread supplied under contract to the Board had stale crusts, cigar buts and candle wicks added to it by unscrupulous bakers trying to extract maximum profit from government contracts. 4 The other arm of the supply system was the Commissariat, a centralised provisioning agency that supplied food during wartime and at home when serious food shortages, such as the Irish Famine, threatened soldiers’ diets. 5

But most soldiers ate food sourced and purchased by their commanding officers. For traders in garrison towns, supplying the local barrack was a profitable enterprise. Under this regimental system there could be considerable variation between units. A conscientious commanding officer could carefully inspect the food purchased for his regiment, to ensure that, for example, the meat was not mostly bone and fat. On the other hand, men under the command of disinterested officers were at the mercy of contractors who hardly had the army’s interests at heart. Some officers realised that two meals a day was a paltry diet for adult men whose duties included standing guard outdoors for many hours. Perceptive commanders also noticed that soldiers drank beer and spirits to assuage their hunger. 6 During the 1830s, many regiments organised a third meal in the afternoon to break the almost 20 hour fast between dinner and breakfast. In 1844, army regulations were changed to reflect this initiative and more bread, washed down with tea or coffee, was served in mid-afternoon but only ‘when the price of provisions and other circumstances admit.’ Unfortunately for soldiers serving in North America and Gibraltar, prices were too high and they went without the third meal. 7

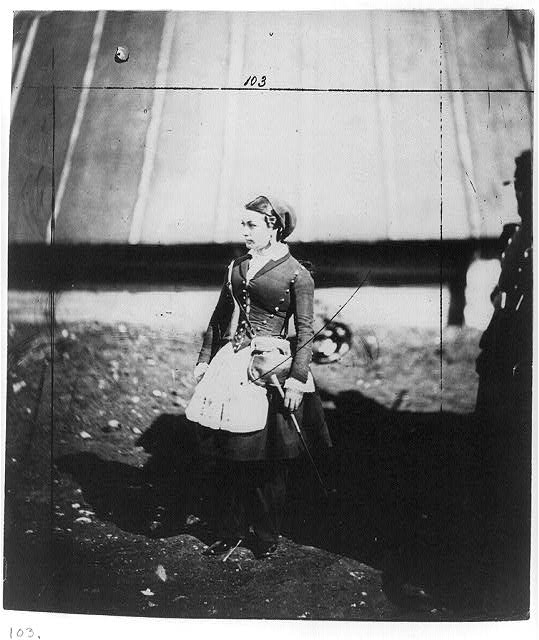

At War in the Crimea 1854-56

When the army went to war in the Crimea, the food supply chain broke down alarmingly quickly. The Commissariat, unaccustomed to provisioning the army at home because regiments so often catered for themselves, could not supply thousands of men and horses in wartime conditions. When travelling, or fighting, soldiers were issued with hard biscuit instead of a bread ration. While the biscuits did not go stale they were unpalatable and difficult to eat without cooking facilities. But the Commissariat and the regiments were slow to establish canteens. Without regular hot food, the harsh Crimean winter was intolerable. In contrast the French army was well-organised: soldiers were fed from canteens and women cantinieres or vivandieres, wearing a modified version of a soldier’s uniform, were an important part of the provisioning system.

While the French refreshed themselves daily with hot coffee, even this was culinary comfort eluded the British soldier, whose coffee ration, unbelievably, was issued as unroasted green coffee beans. 8 (A drink can be made from green coffee beans but it is horribly astringent, with no coffee aroma.) The war correspondent, William Russell, whose reporting exposed the terrible conditions in the Crimea, blamed much of the army’s sickness on ‘exposure, hard work and poor feeding’. 9 The skewed priorities of British commanders were shown when the Commissariat’s pack animals were requisitioned for military use. 10 Without sufficient mules and horses to transport food to depots close to the front line, the Commissariat could not feed the troops. It was a Frenchman and famous cook, Alexis Soyer, who finally tackled the catering problems of the British army. He even invented a fuel-efficient cooking stove, which he believed would save thousands of pounds of fuel per day. 11

After the publicity surrounding the terrible living conditions in the Crimea, a spate of reform initiatives were proposed and implemented in subsequent decades. Sanitation in barracks finally began to improve, as washing facilities were installed and barrack rooms enlarged. But while reformers fretted over the cubic square footage of air allocated to each soldier in a barrack room, the army diet escaped close scrutiny. Until 1874, soldiers continued to pay for their basic meat-and-bread rations. The first Army School of Cookery was established in 1885 but the sergeants cooks were not required to train there until 1890. 12 Food continued to vary enormously between regiments even into the twentieth-century when the War Office observed that officers who made a ‘hobby’ of soldier’s provisioning were responsible for most improvements.13 The story of British soldiers’ rations is as much a story of conscientious leadership as it is of hunger and thirst.

You talk o’ better food for us, an’ schools, an’ fires, an’ all:

We’ll wait for extry rations if you treat us rational.

Don’t mess about with the cook-room slops, but prove it to our face

The Widow’s uniform is not the soldierman’s disgrace.

For it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ “:Chuck him out, the brute!”

But it’s “Saviour of ‘is country” when the guns begin to shoot;

An’ it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ anything you please;

An’ Tommy ain’t a blooming fool-you bet that Tommy sees!

Last verse and chorus of ‘Tommy’, from Rudyard Kipling’s Barrack Room Ballads (1890)

- ‘Barrack Life’ in David Chandler, Oxford History of the British Army (2003), p 173. ↩

- Myna Trustram, Women of the Regiment: Marriage and the Victorian Army (1984), p 30. ↩

- Tony Hayter, ‘The Army and the First British Empire 1714-1783’ pp 112-131 in David Chandler, Oxford History of the British Army (2003), p 117. ↩

- Hew Strachan, Wellington’s Legacy: the Reform of the British Army 1830-54 (1984) p 58. ↩

- Strachan, p 59. ↩

- David French, Military Identities: the Regimental System, the British Army, and the British People, c. 1870-2000 (2005), p 121. ↩

- Strachan, p 58. ↩

- Sir William Howard Russell, The British Expedition to the Crimea (1858), p 46 and 248. ↩

- Russell, p 247. ↩

- Russell, p 231. ↩

- http://www.rlcarchive.org/R0325.pdf, p 20. ↩

- French, p 122 ↩

- French, p. ↩