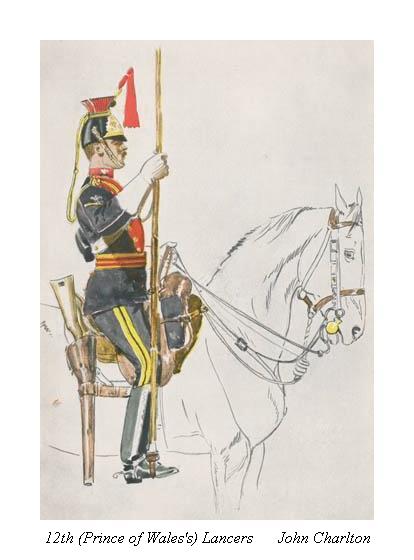

Violence was common during nineteenth-century Irish elections, with rival party factions obstructing voters by fair means or foul. As a result, polling day acquired a ‘military character’, with infantry and cavalry assisting the constabulary in escorting voters and controlling crowds. 1 Using the military as police was risky; sometimes heavily armed men responded to civilian taunts and harassment with lethal force. On 28 December 1866, a hot-headed, unauthorised cavalry charge by the 12th Lancers in Dungarvan left two women widowed and 11 children half-orphans. Yet there were many soldiers on election duty that weekend tramping across the countryside to escort voters from crossroads to polling places. Why did the 12th Lancers break ranks and earn the epithet ‘the Butcher Lancers’?

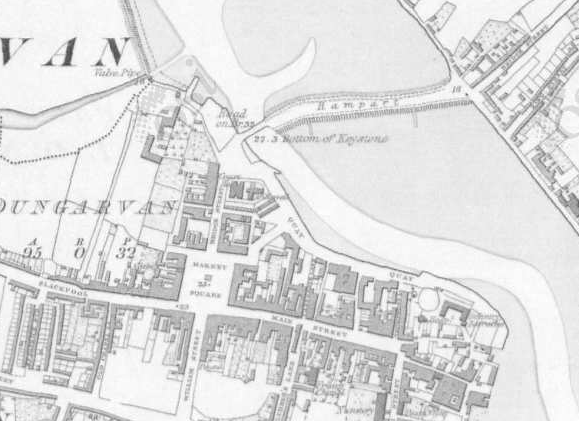

One hundred Lancers and a similar number of infantry were brought to Dungarvan to provide security during a fractious election. 2 When the 12th Lancers approached the bridge to cross into Dungarvan at 2pm, they had been at work since early morning. Like many military men that weekend, they were employed in escorting voters to the polling stations, protecting them from assault and intimidation. Accompanying voters could be tedious and unpleasant, requiring long hours in the saddle punctuated by outbursts of violence. The Lancers had earlier brought in a party of 100 voters into Dungarvan, quelling a bout of stone throwing by riding ‘round and round’ the square. 3 On their second journey, a troop led by Major Adolphus Ulick Wombwell, was split into two parts and placed at the front and rear of the column. Infantry surrounded the voters on all sides as the party approached the causeway over the River Colligan. The magistrate in charge, John Butler Greene, led the column across the bridge, hoping to escort the voters to ‘safe houses’ where they could find shelter.

On the town side of the bridge, a large shouting crowd pressed forward, forcing the soldiers to clear the way for the voters. Major Wombwell deployed his men with a warning ‘Now men, keep steady, and don’t skedaddle’. A Lancer replied ‘Sure, Major, we can’t stand to be battered with stones as we were before; flesh and blood can’t bear it’. Wombwell said ‘We must bear it all; we must be steady’. 4 Unfortunately for Major Wombwell, a group of Lancers charged at the crowd and pursued the people down the quay. Heedless of Wombwell’s efforts to stop them, which included grabbing at horse’s bridles, the Lancers ran riot on Dungarvan’s quay. People jumped into boats on the quayside and hid in coal yards to avoid the charging cavalry. A labouring man, William O’Brien, was knocked down by a Lancer, with one witness claiming the horse was wheeled around by its rider to dance on his prone body. The Harbour Master, Captain Bartholomew Kiely, was standing at his gate awaiting the arrival of Tory voters – they were to lodge in his house – when a cavalry man thrust his lance into Kiely’s chest. O’Brien died from concussion, while a haemorrhage killed Kiely.

According to some witnesses, the cavalry charge occurred after a hail of stones rained down on the column, while others staunchly maintained the people were tranquil until the soldiers charged. Unsurprisingly, eye witness accounts reflected the polarised nature of the election contest between the Tory candidate Captain Talbot and the Liberal Edmond De La Poer. By escorting Tory voters to the polls, the Lancers were inextricably associated with the unpopular candidate’s campaign. The inquests heard that the soldiers and voters were taunted and jeered with ‘party expressions’ such as ‘Down with the Tory’, ‘To hell with the horse soldiers’, ‘Down with the Orange buggers’ and ‘Down with the Lancers’. 5 Civilians gave evidence that the rampaging soldiers shouted ‘ye damned sons of bitches we’ll give it to ye’ at people cowering in boats. 6

During a two-week long inquest, cavalry officers and men gave evidence on the disastrous events of election day in Dungarvan. Major Wombwell was frank about losing control of his troop and how he vainly sought to stop their rampage by grabbing at horse’s bridles. 7 He admitted that he shouted ‘For God’s sake, sound the assembly’ to the regimental bugler, hoping to call his refractory troop to order. When asked to name the men who had broken ranks and charged the populace, the Major reached the limit of his honesty. Wombwell disingenuously claimed ‘I don’t know a man in the whole regiment hardly’, suggesting that he were incapable of ascertaining his subordinate’s identity. He neither enquires who had attacked Captain Kiely nor did he discipline anyone even though he admitted that the troop had broken away without orders. The cavalrymen were protected by their officers who agreed that discipline had broken down but would not identify the offenders to an inquest jury.

After the Lancer’s riot in Dungarvan, terrified Tory voters refused to come to the town to vote. Captain Talbot lost the election and the Lancers continued to work in Ireland after this incident, patrolling the countryside in the early month of 1867 to suppress Fenianism. The regional press loudly condemned the killing of William O’Brien, though the unfortunate Captain Kiely was not poor or nationalist enough to be a ready object of public sympathy. Dungarvan’s worthies started a fund to aid O’Brien’s impoverished family, soliciting donations from clergy, merchants and landowners. Bizarrely, the Town Commissioners wrote to the 12th Lancers for a donation ‘well knowing the officers of the British Army to be always generous’. 8 Cavalry running amuck had not fundamentally changed the military-civilian relationship.

The coroner’s investigation was published in the form of depositions (https://archive.org/details/op1249450-1001) and a verbatim account of proceedings (https://archive.org/stream/op1249484-1001#mode/2up).

For more images of 12th Lancers see the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection https://library.brown.edu/collections/askb/

- K.T. Hoppen, ‘Grammars of Electoral Violence in Nineteenth-Century England and Ireland’ English Historical Review 109: 432 (Jun 1994) pp 597-620. ↩

- Although Dungarvan Castle was a military barrack, the soldiers protecting the voters were drawn from the cavalry station in Fermoy. ↩

- Depositions, p 12. ↩

- Depositions, p 12. ↩

- Depositions, p 22. ↩

- Depositions, p 7. ↩

- Proceedings, p 98-102. ↩

- http://snap.waterfordcoco.ie/collections/ebooks/107381/107381.pdf ↩