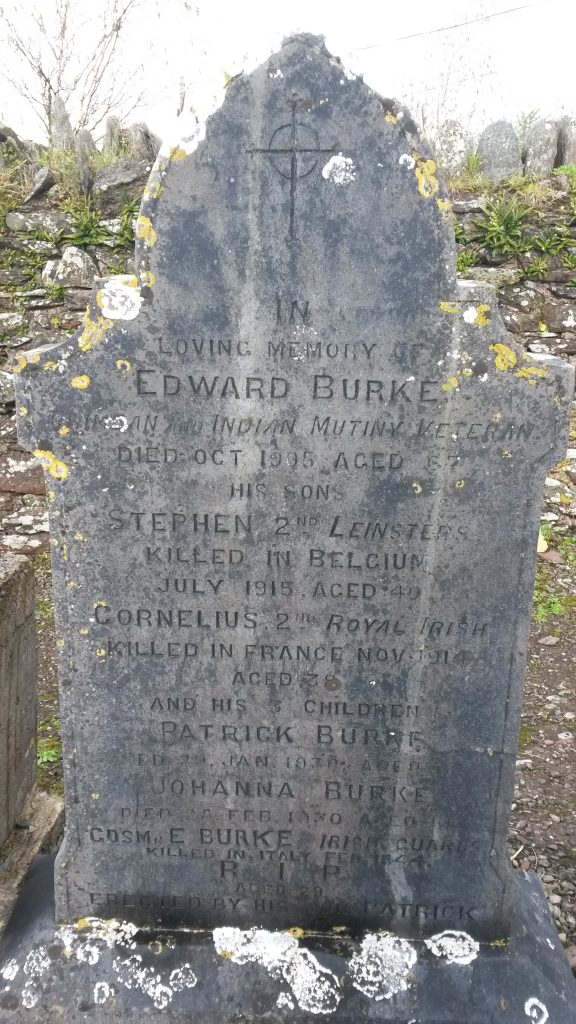

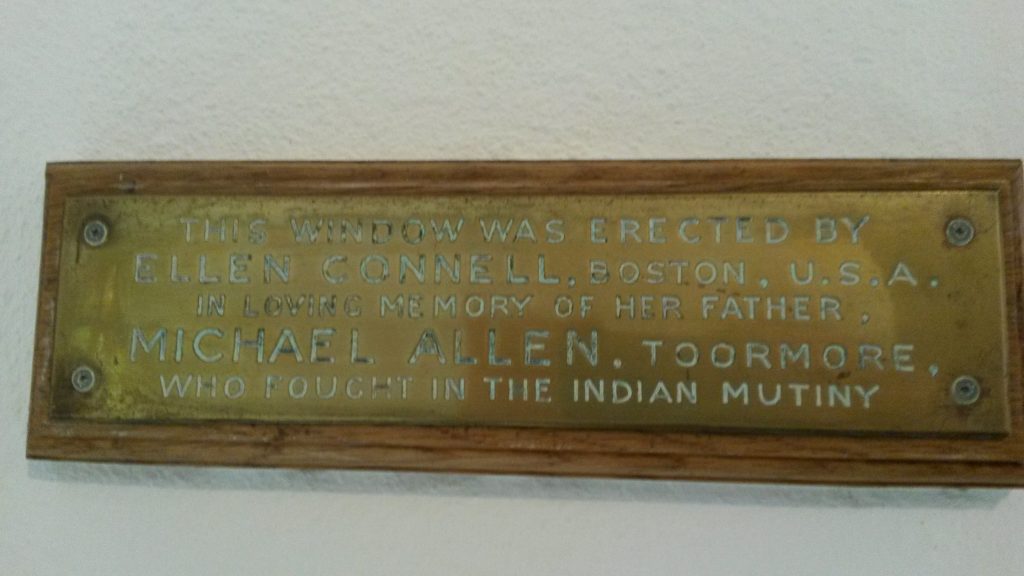

This window, to the memory of Michael Allen who fought in the Indian Rebellion, was placed in Altar Church by his daughter 77 years after that bloody conflict. 1

The Archangel Michael, the warrior saint, crushes Satan beneath his feet before raising his spear to skewer the ghoulish fallen angel. Viewed alongside the explicit dedication plaque, the triumph of the blond, white Michael over the dark-skinned monster becomes a literal representation of the victory of British forces over restive colonial subjects in India. The ‘Indian Mutiny’, 1857-58, entered into British military myth, commemorated in reviews and pageants for decades afterwards. The brutality of rebellious Indians haunted the popular imagination, who lauded the military heroes of Lucknow and Dehli as saviours of European virtue. This window’s explicit colonial message disturbs me, especially because St Michael did not have to be portrayed this way.

Other windows in County Cork show St Michael battling a dragon. In Corkbeg church, named St Michael and All Saints, there are two windows featuring Michael, which commemorate military men. 2 One window shows Michael slaying a dragon, in an image that recalls depictions of St George. (Michael is distinguished from George by his wings.) 3

The dedication reads:

To the Glory of God and in Loving Memory of William Myers Woolsey Priest Sometime Rector of this Parish and his Son Frank of the 23rd Bombay Rifle Regiment. RIP.

Frank died of sunstroke at Raykote in 1892. His father died in Corkbeg in 1881. 4

The other window shows St Michael with a scales, referring to his role in the Last Judgement, when he will weigh the souls. Although he is holding his sword and wearing armour, Michael here is more stern judge than triumphant warrior.

The dedication on this window reads:

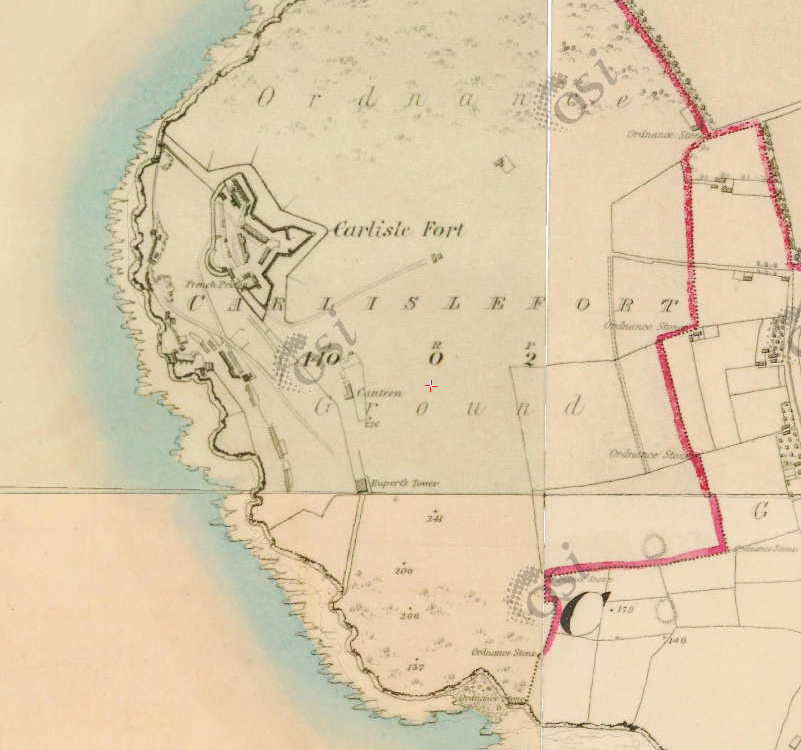

To the Glory of God and in Loving Memory of Frances Edwards who died at Parkstone Dorset Jany 2nd 1895. Also of Frank Hodges Captn in the Clare Artillery and Royal West Regt who died at Fort Carlisle May 22nd 1896. He served in the Soudan with the 50th Regiment and was present at the Battle of Ginnis.

Although this window commemorates colonial service, it is a more equivocal image that invites multiple readings than the St Michael window in Altar.

As well as being named for a warrior saint, Corkbeg church was effectively the garrison church for the nearby Fort Carlisle. The Rector was chaplain to the troops, for which he received 50 pounds a year. He was also the chaplain and visitor to the school in the Fort where soldier’s children were educated. Every Sunday, the Anglican officers and men paraded to their local church, St Michael’s, led by a military band.

St Michael was not a very popular choice for stained glass in the Church of Ireland, featuring in just 39 windows in the Gloine survey. 5 Important biblical stories such as the Angel and Women at the Tomb were depicted in 100 windows, while 171 portrayals of the Ascension are recorded. But the stained glass windows of the warrior saint shows how the glory of war was part of the devotional fabric of some church buildings.

**Corkbeg images are from the Gloine website. There is no equivalent survey of the Roman Catholic churches of Ireland.**

- The window dates from circa 1935. See http://www.gloine.ie/gloine/diocese/building/3223/ ↩

- http://www.gloine.ie/gloine/diocese/window/15284/ ↩

- http://www.christianiconography.info/michael.html ↩

- http://www.corkpastandpresent.ie/history/coleschurchandparishrecords/colesrecordsdioceseofcloyne/cole_cloyne_175_202.pdf p 196. ↩

- http://gloine.ie/gloine/search/window/iconography ↩