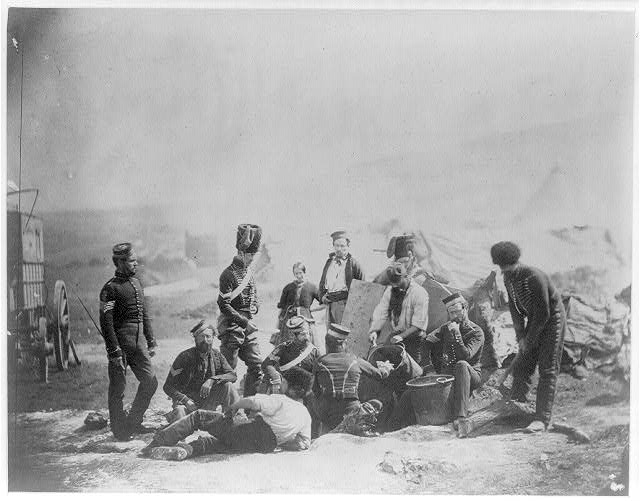

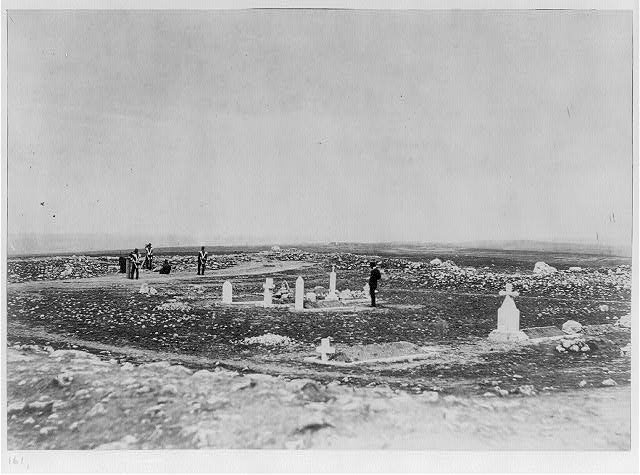

In February 1909, 83-year-old Patrick Hanlon died in Waterford workhouse, but he was not buried in an anonymous grave in the Poor Law Union burial plot.1 The coffin was a ‘nice’ coffin with a breastplate rather than the cheapest ‘shell’ provided by the Union for pauper burials. His remains were placed on a gun carriage and the cortege was led by a firing party, ‘with arms reversed … accompanied by trumpeters who sounded the sad and weird notes of the “Last Post”. Three volleys were fired over his grave, which was dug in St Mary’s churchyard, almost an hour’s walk away from the workhouse. 2 But why all this ceremony for an elderly man who died in the workhouse? Upon Hanlon’s death, the workhouse master, Mr Cosgrave, had written to the War Office to inform them that a venerable veteran of the Crimean War had died. The Veteran’s Relief Fund, established just a year earlier, duly sent £4 to the master cover the funeral expenses. 3 Cosgrave arranged the military honours with the town’s barracks, purchased a coffin and selected a grave site. Thus an elderly man who died a pauper was buried as a soldier.

Men who fought for the Red, White and Blue,

Left to end their last days in the workhouse

When they died – just a pauper’s grave too. 4

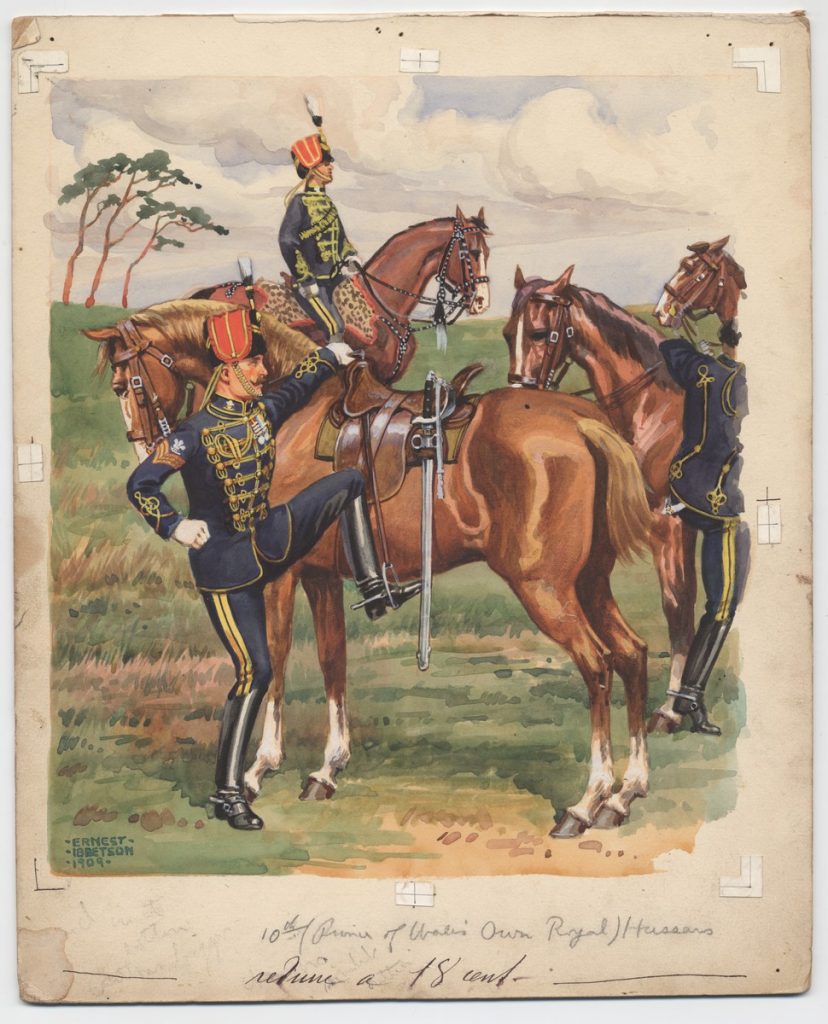

Rescuing old soldiers from the ‘indignity of a pauper’s grave’ was central to work of the Veteran Relief Fund. 5 Established by Lord Roberts in 1908, the Fund aimed ‘to uplift, entertain, remember and rescue’ 6 army and navy veterans, but only if they had enlisted before 1 January 1860 7 (Another Roberts, Mr Thomas Harrison, started a fund in 1897 to aid survivors of the Charge of the Light Brigade, but it did not seem to extend to Ireland.) The Veteran’s Fund was intended to benefit those who had fought in the talismanic imperial conflicts of the nineteenth century, the Crimean War and the ‘Indian Mutiny’ as the Indian Rebellion was known. Kriegel has established how important local committees in provincial England were to the administration of the Fund, but the Irish case is a little different. In Ireland, the Fund was administered from Dublin where staff distributed aid to Leinster, Connaught and Munster, while a Belfast committee administered the Ulster counties. In Belfast, the committee most resembled those found in England, being composed of politicians, former military men, grandees, clergy and local representatives. 8 One Belfast city councillor, George A. Doran, worked so assiduously on behalf of army veterans that he was described as a ‘constant friend of the old soldiers’. 9 He helped to secure military funerals for men who died outside the workhouse, approaching the local barracks on behalf of the bereaved. 10 Doran also lobbied the War Office to grant pensions to old soldiers whose claims may have proved difficult to verify. 11

There is little evidence that similar committees appeared in other Irish cities. Military funerals were organised by the workhouse because the authorities had received a circular from the Local Government Board informing them of the Fund’s purpose. No doubt the opportunity to save money motivated many workhouse masters. These military funerals were extraordinary because the men being interred had not served for decades. Being few in number and great in years, these old men became symbols of the defence of empire. Naturally, strident nationalists were quick to point out how the plight of veterans in the workhouses, ‘the shelters of the outcasts and the paupers’, perfectly illustrated British perfidy. 12 A sarcastic columnist noted that a veteran was consoled by the knowledge that the British army would take the opportunity to ‘advertise itself’ at his funeral. 13 People in garrison towns were familiar with military funerals but the extension of martial pomp to paupers was a novel innovation. Hanlon’s funeral drew a crowd to the workhouse dead house: nurses, inmates, officials, school children and journalists. 14

However, burial with full military honours was not easy to secure. In Waterford, the military party waited outside the workhouse for two hours while Hanlon’s army record was debated. A local journalist observed that ‘telegrams were flying like snowflakes’ as bicycle orderlies travelled between the workhouse and the barracks. 15 Verifying identities was notoriously difficult, especially when at least 38 Patrick Hanlon’s served in the Crimean War. 16 Luckily for Hanlon, his army record was proven and his grand military send-off proceeded as planned. The Veteran’s Relief Fund was instrumental in saving old soldiers from workhouse cemeteries across provincial Ireland. An army funeral leaving a workhouse was an incongruous sight but one that illustrated the cultural militarism of a ‘bellicose era’. 17

- St Otteran’s cemetery, on the Cork Road, contained the workhouse burial plot. http://www.waterfordcouncil.ie/departments/culture-heritage/family-history/graveyards/st-otterans.htm. ↩

- Munster Express, 27 February 1909. ↩

- Munster Express, 27 February 1909. ↩

- Excerpt from ‘Take Care of Tommy’ by Henry A. Magee, Westgate, Dunmurry. Weekly Telegraph, 12 August 1916. ↩

- Northern Whig, 1 April 1908. ↩

- Lara Kriegel, ‘Living links to history, or, Victorian veterans in the twentieth-century world’ Victorian Studies vol. 58. No. 2, p 293. ↩

- Northern Whig, 1 April 1908. ↩

- Northern Whig, 1 April 1908. ↩

- Northern Whig, 21 April 1915. ↩

- Northern Whig, 21 April 1915. ↩

- Northern Whig, 1 April 1908. ↩

- Donegal News, 7 December 1907. ↩

- Limerick Leader, 2 March 1908. ↩

- Munster Express, 27 February 1909. ↩

- Munster Express, 27 February 1909. ↩

- See https://www.forces-war-records.co.uk/ ↩

- David Fitzpatrick, ‘Militarism in Ireland’, p 379 in Thomas Bartlett and Keith Jeffreys (eds), A Military History of Ireland (1996). ↩