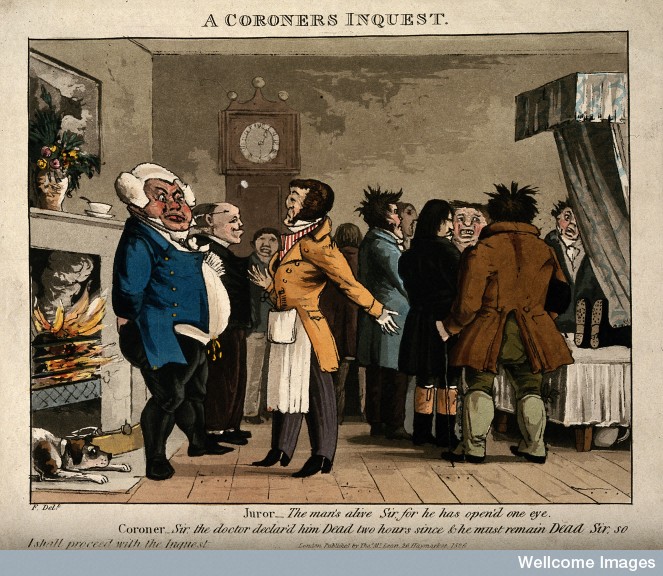

On a grey February Monday in 1867, an inquest jury of 12 Limerick men met in the hospital of the New Barracks, to investigate the death of Private Robert Sim ‘then and there lying dead’ before them. Sim, of the 74th Highland Regiment, had died 2 days earlier, from ‘congestion of the brain, occasioned by erysipelas’ according to the military surgeon Charles John White. 1 (Erysipelas is an acute bacterial infection of the skin, most frequently occurring on the face in this time period. 2) So why did Sim’s death warrant a coroner’s investigation? Before the discovery of antibiotics, even the strongest individual could die from an infection, or the accompanying fever. Inquests were convened when the coroner had doubts about the cause of death, and these suspicions were generally aroused by a report from a clergyman, a policeman or a local government official. For Sim’s was no ordinary case of sudden fever: 17 days before his death he had been taken the barrack square, tied to the halberds and lashed fifty times with the cat o’ nine tails. The sounds of flogging – the drum beat to keep time for the flogger, the groans of the man under the lash – may have echoed through the streets around the barracks, as it had in Castlebar in 1845. Limerick Coroner John Gleeson called the inquest on Sim’s body because he, and others in the city, suspected that the Private’s death was something out of the ordinary.

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The inquest called 5 military witnesses: two NCOs (non-commissioned officers) responsible for running the military prison and hospital respectively and three regimental surgeons. The officer commanding the regiment, Colonel William Kelty McLeod, was also present and participated. The jurors questioned each witness, their inquiries revealing their collective concerns about the medical care offered to Private Sim after the flogging. The NCOs were asked about the practice of sending flogged men to jail rather than prison, while the surgeons were asked about whether doctors supervised floggings (they did) and if military prisoners were visited daily by medical officers (they were). Of course, the jury’s main concern was what had caused the death of Robert Sim. Military surgeon Charles White, who had examined Sim’s body, stated that the soldier died of erysipelas, but the jurors were not so sure. The foreman of the jury asked whether the infection was caused by the flogging Sim had endured but White refuted this, pointing to the length of time between the punishment and the onset of infection. He also said ‘I cannot say whether the death of the deceased was accelerated by the punishment he underwent; I should say it had very little or nothing to do with it.’ 3 By the time Sim was seriously ill, his back presented ‘a perfectly healthy appearance’.

But Sim’s body was also examined by a civilian doctor, Dr Jonathan Elmes. He agreed with the diagnosis of erysipelas, having seen inflammation on the head and face consistent with the disease. Elmes also noted abrasions on the skin between the shoulders ‘probably the remaining marks of punishment’. His verdict on Sim’s death was ‘irritative fever, with the concomitant congestion of the brain’, which was in agreement with Surgeon White. However, under questioning from the jury, Elmes offered a medical opinion at odds with White’s: ‘I have no doubt but that the punishment the deceased underwent led to the train of symptoms which led to his death.’ 4 The jury now had two contradictory assertions from medical professionals who agreed erysipelas had killed Sim, but differed on whether the flogging had affected his health. They had viewed the body, listened to the evidence and questioned the witnesses. The jury of 12 Limerick men reached a startling conclusion; that Sim died from fever ‘accelerated from corporal punishment he received, as the result of a district court martial.’ 5 This finding blamed the death of Private Sim not on any medical deficiency in his care but on the flogging he received 17 days before he died. It was not the verdict Colonel McLeod wished to hear.

When the inquest ended, the body of Private Sim was taken from the New Barracks to be buried in the military graveyard. An ‘unusually great’ crowd of civilians followed the cortege from the barracks to the military graveyard on the northern edge of the city. According to the Limerick Reporter, these were mostly from ‘the humbler class’, a section of society the editorial writer believed ‘are by no means undiscriminating admirers of British soldiers’. Yet many attended Sim’s burial, showing their sympathy with his fate by their conduct and demeanour. 6 The presence of so many civilian mourners shows how widely the news of Sim’s death and the coroner’s inquest had spread in the city, for the funeral did not start until the inquiry had closed. Limerick people had waited outside the barrack for the inquest to finish, in order to follow Sim’s coffin to the graveyard.

The knowledge of the soldier’s punishment and death was not confined to the coroner and those men with enough property to be eligible for service on his jury. Since Sim was a Presbyterian, the public interest cannot be explained by any fraternal denominational feeling, for Limerick was an overwhelmingly Catholic city.

The next day, the verdict was reported in the Limerick, Tipperary and Cork press, and over the next few weeks the story featured in other newspapers in provincial Ireland. Later that week, the Limerick Reporter even published an editorial piece titled ‘Scourging soldiers in Limerick garrison’. In a year where Fenianism and the threat of rebellion once again occupied minds the writer pointed out that Sim was ‘punished more severely than the most decided Fenian’. (In his time in Limerick, Sim may have been part of the ‘flying columns’ formed by the 74th to police the surrounding countryside for Fenians. 7) He even claims that further horrors await: another flogged soldier in Limerick barracks is so ill ‘that his death maybe expected at any moment’.

The fate of Robert Sim had not escaped the notice of members of parliament who were opposed to flogging, and who annually challenged the Mutiny Bill clause on corporal punishment. Since Francis Burdett had made it a feature of the annual army vote, a succession of leading reformers had taken up the cause.8 By the 1860s, decades of persistent agitation had begun to bear fruit: in 1863 and 1864 the government won the vote to retain flogging in the army by just 2 votes.9 In 1867, the House of Commons debated the Mutiny Bill a few weeks after the Limerick jury’s verdict. In proposing that the government abolish flogging in the army in peacetime, Sir Arthur Otway referred to Sim’s death saying, ‘if it were possible that death should result from the punishment, the punishment ought to be abolished altogether.’ 10 For the first time ever, the government lost the vote and Otway’s motion to restrict flogging to wartime passed. Two weeks later, the Limerick jury petitioned the House of Commons to establish an inquiry into the punishments inflicted in the 74th Regiment and the many desertions from it.11

Unfortunately for the average British soldier, flogging in the peacetime army was not abolished in 1867. Due to the system of amendments and counter-amendments that characterizes the House of Commons, the government won the final vote on the corporal punishment clause of the Mutiny Bill. The system was so opaque that some MPs may have voted the wrong way: Sir George Bowyer complained that he had overheard members in the lobby outside the chamber trying to work out which way to vote.

‘He heard many hon. Members around him ask the questions, “Are we voting right?” “Are we voting for the ‘ayes’ or for the ‘noes’?” and he heard one hon. Member say, “I am voting for Otway,” when in reality he was voting against him.’ 12

However, Otway was not discouraged and his resolution to abolish flogging in peacetime was inserted into the Mutiny Bill in 1868. The verdict of the Limerick inquest jury, arguably more about the politics of army punishment than the medical facts of the case, showed that the public revulsion over flogging could force legislative change on a reluctant army. Wartime court martials lost the power to sentence British men to flogging in 1881, though African troops in the British army were flogged until 1946. 13 The death of Robert Sim in Limerick and the jury’s determination to condemn flogging had a direct effect on the disciplinary system of the British army.

- House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, ‘Robert Sim. Copy of the depositions of the witnesses and the verdict of the jury upon the inquest held on 11th February last, by John Gleeson, Esq., in the hospital of the new barracks, Limerick, upon the body of Robert Sim, a private of the 74th Highlanders, who died in the said hospital on Saturday, 9th February 1867, after receiving a flogging in the open square of the said barracks, on 19th January previous, pursuant to a sentence of court martial’, p 3. ↩

- http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1052445-overview. ↩

- Robert Sim Deposition, p 3. ↩

- Robert Sim Deposition, p 4. ↩

- Robert Sim Deposition, p 1. ↩

- The Limerick Reporter and Tipperary Vindicator, 15 February 1867. ↩

- Sir John Scott Keltie et al, A History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments Volume 8, (Edinburgh & London, 1875), p 613. ↩

- J.R. Dinwiddy, ‘The early nineteenth-century campaign against flogging in the army’, The English Historical Review, Vol. 97, No. 383 (Apr. 1982), p 308-333. ↩

- http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1867/mar/28/mutiny-bill-committee#S3V0186P0_18670328_HOC_129 ↩

- http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1867/mar/15/resolution#S3V0185P0_18670315_HOC_80 ↩

- The Lancet, Vol 92 (1867), p 408. ↩

- http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1867/apr/01/mutiny-bill-committee#S3V0186P0_18670401_HOC_85 ↩

- Arthur Grundlingh, War and Society: Participation and Remembrance South African Black and Coloured Troops in the First World War, 1914-18 (Sun Press, 2014), p 70. ↩