According to a 1907 account by an army chaplain, Rev. E.J. Hardy, soldiers ate well on Christmas Day. 1 The usual boiled beef or mutton was served alongside goose, turkey, ham and pheasant. Unfortunately this abundant repast was eaten cold because the barrack cookhouse and its staff were not able to cook such a variety of food in just one day, especially when it was served in the early afternoon. In order to have the meal ready, preparation of the Christmas feast had started a few days before the 25th. Cold food notwithstanding, the ordinary soldier greatly appreciated the range of meats on his table. He ate copious condiments and pickles with his meat; one man thought pheasant ‘tasteless stuff’ without mustard.

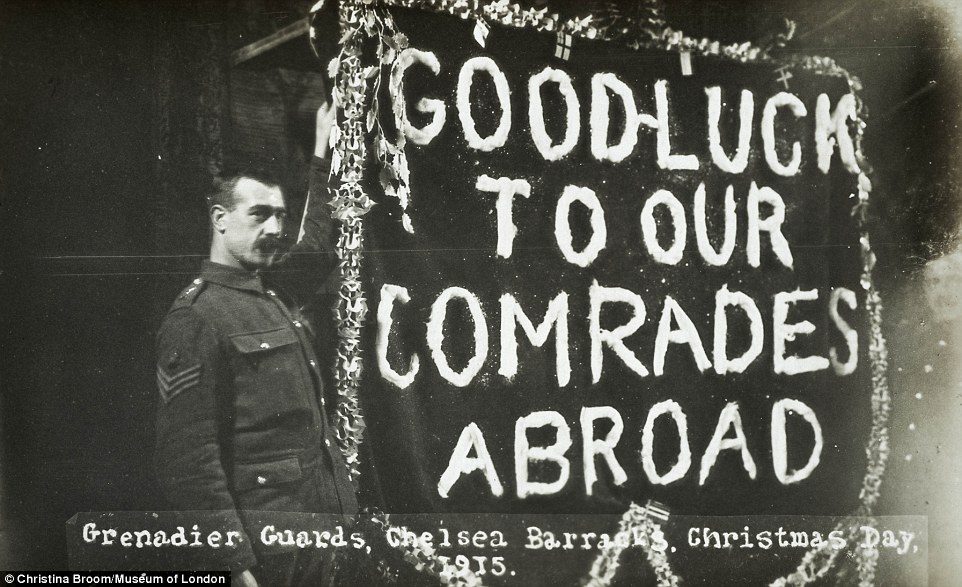

The barrack rooms in which soldiers lived and ate were transformed by homemade decorations. Alongside the holly and the ivy, coloured paper streamers hung from the ceiling. The bare white-washed walls were enlivened with festive slogans painted in gilt by an artistically talented soldier. What would have been graffiti and liable for barrack charges the rest of the year was embraced and celebrated as art at Christmas. Some common messages included: ‘To Our Comrades Abroad – God Prosper Them’, ‘A Health To Everyone’, ‘At Peace, but Still On Guard’ and ‘At Rest, But Ready’. There were also joking references to life in the barrack. A room where the regimental drummers dined together was decorated with the ‘Drummer’s Restaurant’, while over the door of the guard room where the same men were arrested again, and again, was painted ‘There’s No Place Like Home’.

In spite of the holiday, soldiers were obliged to work on Christmas Day. In the cavalry, the horses had to be fed, watered and cared for as usual. Even the Church Parade on Christmas morning was work, as men attended church in immaculate parade order, the army equivalent of Sunday best clothes. Dressing in parade-order uniform took a lot of time and demanded fastidious attention to detail. 2 Throughout the day, a portion of men had to be ready for guard duty or to form a piquet, a group of armed men poised to respond to an alarm, at all times. At Christmas, there was a danger that over-consumption of alcohol would leave the men incapacitated. Hardy claimed that excessive festive drinking had been a problem in the 1880s when he first joined the army, but that matters had improved enormously by 1907.

Luckily, most routine duties were suspended on Christmas Day. The soldiers and NCOs who worked in the officer’s mess, serving table and keeping the books, had a day off because, to give the staff a holiday, officers generally dined out. Many officers were not in barracks at Christmas because they had the means to travel home during their winter-time furlough. As trains became cheaper and quicker, more ordinary soldiers also travelled home to visit their friends and relations. For those remaining in the barracks, the post-dinner hours weighted heavily upon them. Inevitably, contests of all kinds were started to divert the mind and body. Officers in the 78th Regiment dusted down the mess betting book: on Christmas Day 1824 Mr Cooper and Mr Wilson wagered 1 bottle of port that Cooper would consume a bottle of beer with a spoon while Mr Wilson ate a dry penny roll. (Cooper won this bet.) 3 Soldiers played informal games of football, organised sing-songs or dancing. Occasionally, the long hours after a large meal and generous amounts of alcohol were marred by fighting. Two men in the Curragh argued over which of their respective regiments had travelled furthest up the Nile, and their personal dispute nearly escalated into a brawl between the different regiments. Boxing Day or St. Stephen’s Day, 26th December, was also a holiday though no sumptuous meal was served. More football was played by the soldiers, while officers with a passion for hunting could ride to hounds with a local pack.

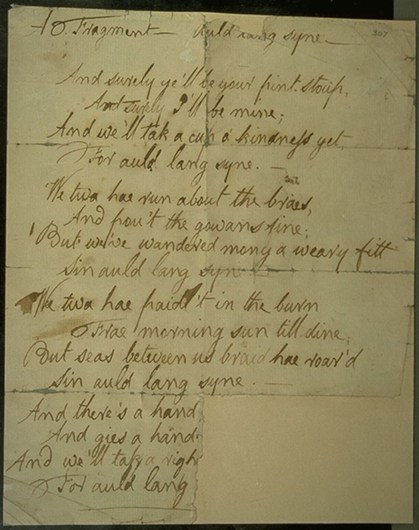

But the observation of Christmas was not uniform in the British army, as regimental identity and tradition separated the Scottish units from the rest. Scottish soldiers were relatively indifferent to Christmas day, but celebrated New Year’s Eve, or Hogmanay, with great gusto. This distinctive holiday pattern originated in the Scottish Kirk’s disapproval of Christmas as ‘popish’, an attitude which did not change even as Victorians embraced the festival. 4 In his memoir, Scottish soldier John Pindar waxes lyrical on the wine-house conviviality of New Year’s Eve with his comrades. 5 Scots frequently took on extra duties during 25th and 26th December, allowing their English and Irish colleagues time to celebrate. The favour was then returned on New Year’s Eve and Day. 6 Whatever the regiment or the festival, the army strove to find a balance between festive cheer and military discipline, between personal gratification and institutional demands.

- Rev. E. J. Hardy, ‘Christmas in the Army’, Belfast Weekly News 19 December 1907. This article appeared in a number of newspapers that year. ↩

- Compulsory Church Parade was only abolished in 1946 Jeremy A. Crang, ‘The Abolition of Compulsory Church Parades in the British Army’ Jrnl of Ecclesiastical History vol. 56, issue 1, (2005) pp 92-106. ↩

- Graham Sharpe Gamblings Strangest Moments ‘A Mess of Bets; Officers Mess 1822-1908’ ↩

- http://www.scotsman.com/heritage/people-places/christmas-and-new-year-traditions-in-scotland-1-3226062 ↩

- John Pindar, Autobiography of a Private Soldier (Fife, 1877), pp 98-106. ↩

- Pindar, p 110. ↩