On Easter Monday, 24th April, the staff of the Hotel Metropole on O’Connell Street were surprised to see a party of armed uniformed men enter the premises. Brandishing their guns at the manager, the men demanded all the cooked meats and bread from the kitchens. As the provisions were carried to the neighbouring building, the rebel headquarters in the General Post Office, the leader paid for the supplies with paper notes, later assumed to have been ‘liberated’ from the post office. Over the next few days, the rebels stopped food delivery vans and confiscated their contents at gunpoint. Some unlucky deliverymen were given receipts from the ‘Irish Republic’, 1 stating how much they were owed but most of the 2,000 rebels did not have time for bureaucratic niceties. 2

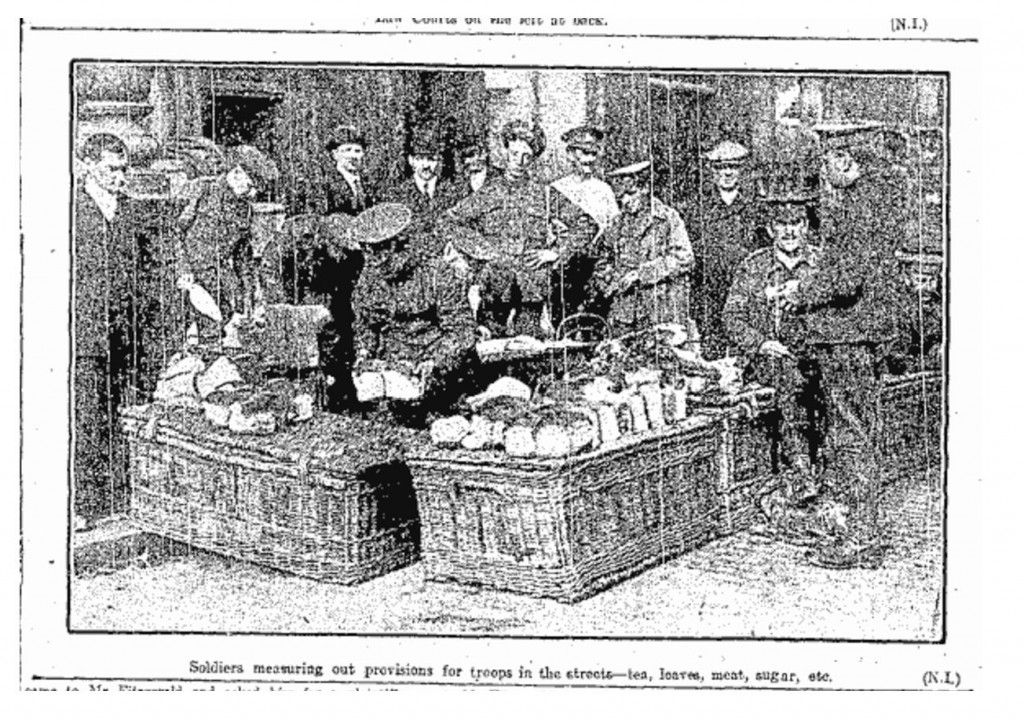

While the rebels found food by any means possible, the British military faced the challenge of feeding large numbers of troops, as thousands of reinforcements joined the 2,312 men already in Dublin barracks. 3 The declaration of martial law on Tuesday 25th April helped the army provision itself because it gave the military complete control over economy and civil society. Soldiers were the first to be fed, and the army commandeered what it needed from wholesalers and distributors who willingly acceded to their demands. 4 As reinforcements poured into Dublin from the Curragh, Belfast and England throughout the week, the army’s need for food grew exponentially. The increased military demand, the cordon that was placed around the city centre, and rebels taking food at gunpoint, halted ordinary food distribution. With both state and rebel armies absorbed in the battle for streets and food, the civilian population were temporarily ignored.

Since every household bought fresh bread daily, a bread shortage was almost immediate. A large city centre bakery, Boland’s, had been occupied by the rebels, making the scarcity more acute. Desperate civilians, even in the embattled city centre, had no choice but to venture out to find bread. Queues formed outside bakeries from as early as 6am. 5 The remarkable sight of staid, throughly respectable professional men carrying cauliflowers or bread loaves amused passers-by during a difficult week. 6 Suburban residents may have been safe from bullets but the people of Howth, who received all their bread from the city centre, were forced to send to Drogheda for supplies. 7 The suburb of Ballsbridge was fortunate to have a bakery – Johnston, Mooney and O’Brien’s – in the area, which continued to bake throughout the insurrection. In a remarkable gesture, the bakery did not raise their prices, selling at normal, pre-Rising rates. 8 In general, scarcity drove prices up: butter prices more than trebled until supplies ran out and margarine was substituted. 9

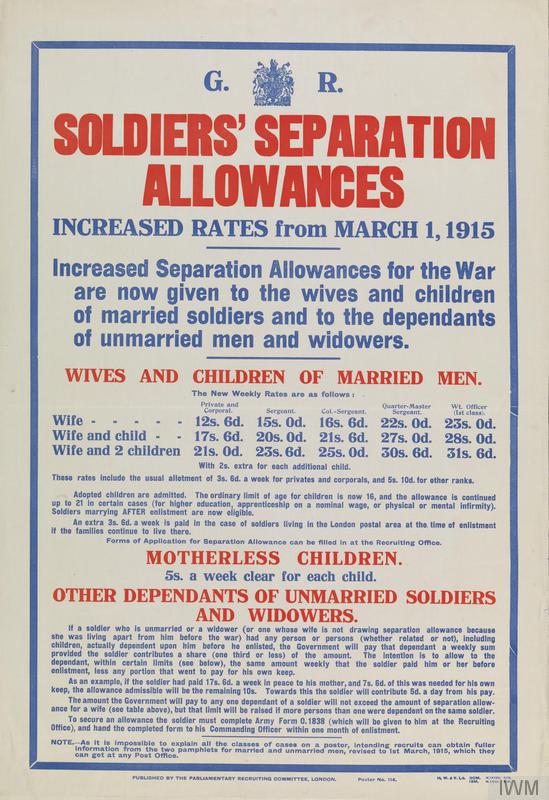

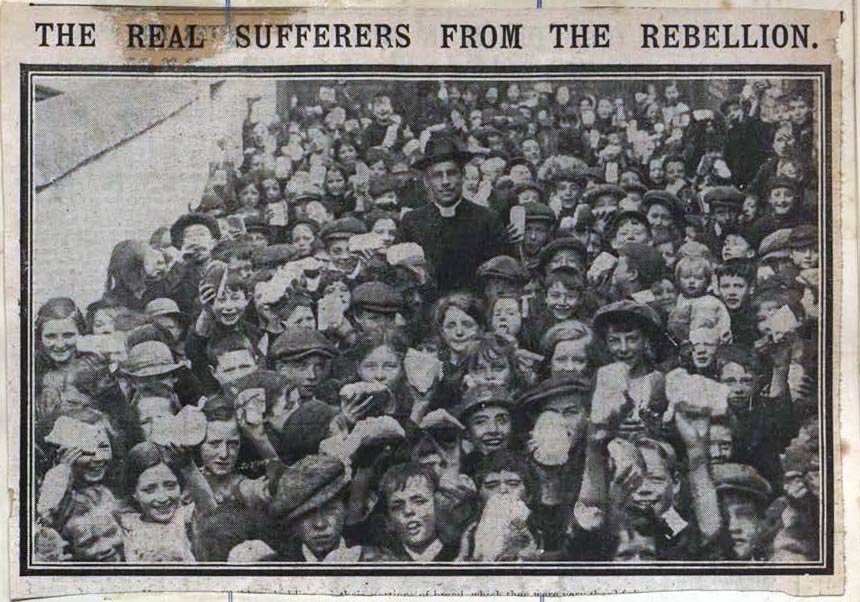

Of course, food prices were irrelevant to the those who had no money whatsoever. When the rebels captured the GPO, they commandeered the money intended for the families of serving British soldiers. The separation allowances were a lifeline for the Dublin poor, who endured wartime price rises with little corresponding increase in wages or job opportunities. During the Easter Rising, service families who lost their income became desperate. By Friday 28th April, privation had become starvation: ‘At almost every shop … women could be heard begging in vain for a single loaf or a drop of milk for their starving children.’ 10 Outside the besieged city centre, the poor raided market gardens for vegetables. 11

At the start of Easter Week, the army was too busy to bother with civilian needs, apart from an emergency distribution of Bovril to hungry Dubliners. 12 Once military success was assured, the army began supplying the civilian population with food. By Saturday 29th, the day of the surrender, the military were delivering supplies to local committees in the food-deprived suburbs of Rathmines and Terenure. 13 Bureaucratic attention turned on the poor on Friday 28th, when the army agreed to deliver food to depots run by the St Vincent de Paul, who would distribute the aid to the needy. In Fairview, the Army Service Corps handed out food to the hungry. 14 As well as supplying free food to the poor, the army continued to control food distribution in Dublin in the week after the Rising. Military transports delivered provisions to ‘responsible traders’, attempting to control prices by supplying only those shopkeepers who would not ‘mulct’ their customers.

But the army faced a food problem that was more politically pressing than organising a city-wide distribution system and feeding over 16,000 soldiers. 15 After the rebel surrender, about 1,000 insurgents who were detained by the army in Dublin had to be fed 3 times a day. There were regulations to interpret, accounts to be kept and all with an eye to the highly charged context surrounding feeding and politics. Suffragettes had begun hunger strikes in 1909, many of which were ended by brutal, life-threatening force feeding by prison authorities. James Connolly, a captured rebel leader, had gone on hunger strike three years previously during the Dublin Lockout. 16 Furthermore, the treatment of Irish dissidents in British detention had long been a sensitive political issue. 17 Five years after his conviction, the prisons conditions of the Fenian, O’Donovan Rossa, were still scrutinised in Ireland: rumours in February 1870 that he had been flogged shocked the nationalist press.18 In the case of the Easter Rising, with the Great War raging in Europe and martial law in force in Ireland, the civil government had allowed the army to assume complete control of the response to the insurrection. Fatally for the 16 executed rebel leaders, the government did not regain control immediately after the rebel surrender. Like the soldiers on the Front, the rebel leaders were subject to the swift and brutal punishments dispensed by the British army at war. 19 It was 20 May before General Maxwell agreed to seek the Prime Minister’s permission before executing prisoners.20 Once the executions ended, the army’s attitude to rebel prisoners in its custody became conciliatory, as proved by the ration plan drawn up in Richmond Barracks.

Per day, each prisoner received:

1 lb. of Fresh Meat

1 lb. of Bread

1 lb. of potatoes or other fresh vegetables

4 ozs of Bacon

4 ozs Jam

4 ozs Margarine

3 ozs Sugar

3 ozs Cheese

1 oz. Tea

1/2 oz. salt

1/50 oz. of pepper

1/4 pint of Milk

Based on the standard ration issued to British soldiers, 21 this allocation included margarine and fresh vegetables that were not usually given to men in uniform. But this ration could be further improved if the officer in charge decided that more ‘comforts’ were necessary. The letter describing the rations concludes with an incredible phrase ‘to be supplied regardless of expense’, proving how extraordinary the political circumstances were after the Easter Rising. 22 The British army, ever conscious of the Treasury, never spent money with abandon.

Prisoners did benefit from this permissive rationing. Between May and June 1916, the officer in charge of prisoners’ supplies in Richmond Barracks authorized extra bread and potatoes, the staple foods of prisoners who were, in his opinion, ‘largely from the peasantry’. They also received extra milk, sugar and cheese. On fast days, the prisoners were fed fish and tinned salmon ‘in deference to [their] religious convictions’. The considerate and generous feeding of the rebel prisoners was ‘to be done regardless of expense, to avoid complaints on the part of prisoners.’ 23 Without doubt, the army was aware of the political sensitivities around Irish rebel prisoners in British custody. These comfortable conditions were intended to preempt any publicity that rebels sympathisers could exploit if the prisoners were mistreated.

Unlike civilians outside the barrack walls, the rebels were assured of a daily breakfast, dinner and supper. They were undoubtedly luckier than inner-city Dubliners who struggled to feed their families in the aftermath of the Rising. Such was the distress caused during Easter week that the Poor Law system offered relief from 8th May to the poor ‘without involving them in any disability’. 24 Here too, fiscal prudence was set aside, and cash payments were made without the usual parsimony. Was this a humane response to deprivation or part of the civil government’s conciliatory policy towards Ireland? Although the army continued to manage the logistics of Dublin’s food supply, the power to feed the people was firmly back in civilian hands.

- Feeding the Rebels, Cork Examiner 3 May 1916. ↩

- On acquiring supplies see Ann Matthews, The Irish Citizen Army (2014), pp 97-8. Figures for rebel forces, Matthews, p 104. ↩

- Matthews, The Irish Citizen Army, p 105 and 106. ↩

- The Food Supply, Cork Examiner, 3 May 1916 ↩

- The Food Supply, Cork Examiner, 3 May 1916. ↩

- This was sufficiently humourous to be reported twice: The Food Supply, Cork Examiner, 3 May 1916; Supply of Bread, Cork Examiner 4 May 1916. ↩

- Report by Special Correspondent Valentine Heywood, Cork Examiner 3 May 1916. ↩

- Supply of Bread, Cork Examiner 4 May 1916. ↩

- The Food Supply, Cork Examiner 3 May 1916. ↩

- Report by Special Correspondent Valentine Heywood, Cork Examiner, 3 May 1916. ↩

- The Food Supply, Cork Examiner, 3 May 1916. ↩

- Incidents of the Rebellion, Cork Examiner, 4 May 1916. ↩

- The Food Supply, Cork Examiner, 3 May 1916. ↩

- The Food Supply, Cork Examiner, 3 May 1916. ↩

- Troop figures here: http://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/patrick-bury-how-the-rebels-could-have-won-in-1916-1.257601 ↩

- http://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/blog/union-leader-james-connolly-on-hunger-strike-in-mounjoy-prison ↩

- Sean McConville, Irish Political Prisoners 1848-22: Theatre of War (2003). ↩

- Cork Examiner, 15 February 1870. ↩

- For more on the legal basis for the rebel’s execution see http://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/the-state-the-law-and-political-imprisonment-1914-1918 ↩

- McConville, p 431. ↩

- http://wwi.lib.byu.edu/index.php/British_%26_German_rations. ↩

- H. Fraser Lt. Colonel, Provost Marshall, Richmond Barracks to The A.D.S.T., Irish Command, undated, WO 35/69/4. ↩

- Lieut. G. Wynn Rushton to A.D. of S.&T., Irish Command, Supply Account of Sinn Fein Prisoners for the period 14/05/15 to 15/06/16, WO 35/69/4. ↩

- Dublin’s Food, Cork Examiner, 4 May 1916. ↩