Time for some reflections on the tourist legacy that garrison towns can exploit. This year, I visited Kilkenny and Cork barracks museums, then Spike Island in Cork Harbour. Each visitor attraction tells a unique story, though Spike Island is by far the most complicated historic site and a fascinating example of garrison town tourism.

Cork Harbour, the second-largest natural harbour in the world, has a long naval history. The great forts at the harbour’s mouth, Camden and Carlisle (renamed Forts Meagher and Davis by the Irish state) are a physical manifestation of the strategic importance of Cork to the British army and navy. From this harbour, British forces provisioned and recruited for overseas campaigns, such as Sir Charles Grey’s expedition to the West Indies. Thirteen ships, full of troops recruited in Ireland, left the harbour in November 1793 for Barbadoes. 1 Fort Westmoreland, now called Fort Mitchell, was constructed on Spike Island between 1804 and 1860. The fort has been a barracks, a deportation point for convicts transported to the colonies, a labour camp, a civilian prison and a military prison. The tour I took was very entertaining, headed by a local man who had also served on the island as a young soldier. His personal reminiscences, told with great style and distinctive Cork humour, were the most memorable part of the tour. We giggled when he told us how, as a young recruit, he whitewashed the coal so that any midnight thefts by the civilian population resident on the island (known as ‘boat people’) could be detected the next day.

But the island’s story is so complicated that our guide struggled to convey it. He also had to stick to the official narrative, laid out online and in the pamphlet we were given. 2 Unfortunately, this meant we were treated to a 10 minute exposition on the life of Little Nellie of Holy God, a soldier’s child who achieved local fame for her piety.

To the non-Irish, non-Catholic tourists, this part of the tour is mystifying. Even in Cork, Little Nellie has faded from popular consciousness. The Good Shepherd convent where she died and was buried is abandoned and derelict. And if this story is intended to appeal to children, it is badly chosen. What parent on a family outing wants to discuss the painful, lingering death of a five-year old?

The disjointed architecture of the fort itself was striking: the massive nineteenth-century fortifications make a curious contrast with the twentieth-century prison fences and barbed wire.

Every type of lawbreaker, from the patriot John Mitchell (1815-75) to the notorious criminal Martin Cahill (1949-94), has been imprisoned in the fort. Young twentieth-century car thieves, known as ‘joyriders’, were held in the same place as men and women convicted of petty theft in the nineteenth century. Convict transports left Spike in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries: first to Barbadoes and subsequently to Australia. 3 There were 2 serious prison riots on the island: one by Irish Volunteers in October 1921 4 and another by civilian prisoners in 1985. 5 How can we tie these stories together? In Irish popular culture, the republican prisoners of the 1920s were heroes, while the young male joyriders incarcerated on Spike in the 1980s were ‘scumbags’. 6 How Spike Island has been a prison for criminals and malcontents for two centuries, continuing its penal function under the Irish state, invites us to contemplate definitions of crime and society. Are all criminals equally, well, criminal? While the state has might on its side, does it have a monopoly on justice? Obviously, a tourist experience isn’t the place for deep contemplation – that would be a real downer on a family day out. The Council is still working on a development plan for the island, so perhaps the narrative will become more reflective. 7

Other military sites with visitor attractions can tell difficult local stories with regard to the international context. Both Cork and Kilkenny barracks – working military barracks – have small museums on site that sensitively describe the buildings and the people. Kilkenny (called James Stephens’ Barracks) is a superlative example of a successful fusion of local and military history, where tales of local soldiers are told alongside displays of debris from World War I battlefields. The history of the Royal Irish Regiment, which was ‘tied’ to Kilkenny under the Cardwell army reforms, is movingly told. A sense of attachment to the past and the long-dead soldiers of the Royal Irish Regiment is genuine. Particularly evocative, and unique, are the standards of the Royal Irish Militia hanging from the ceiling.

As Kilkenny barracks was never a prison, the story is a little less complicated than that of Spike Island. But describing Irish men joining the British army – willingly and in large numbers – is never easy, because in Ireland today, we find it hard to believe that our ancestors could see the British army as anything other than an oppressive and colonising force. If Irishmen joined it, and Irishwomen married soldiers, that may imply that they didn’t have a problem with being British. Of course, the exhibition doesn’t make this point explicitly, but neither does it endlessly repeat that the Irish joined only because they wanted the ‘Queen’s Shilling’.

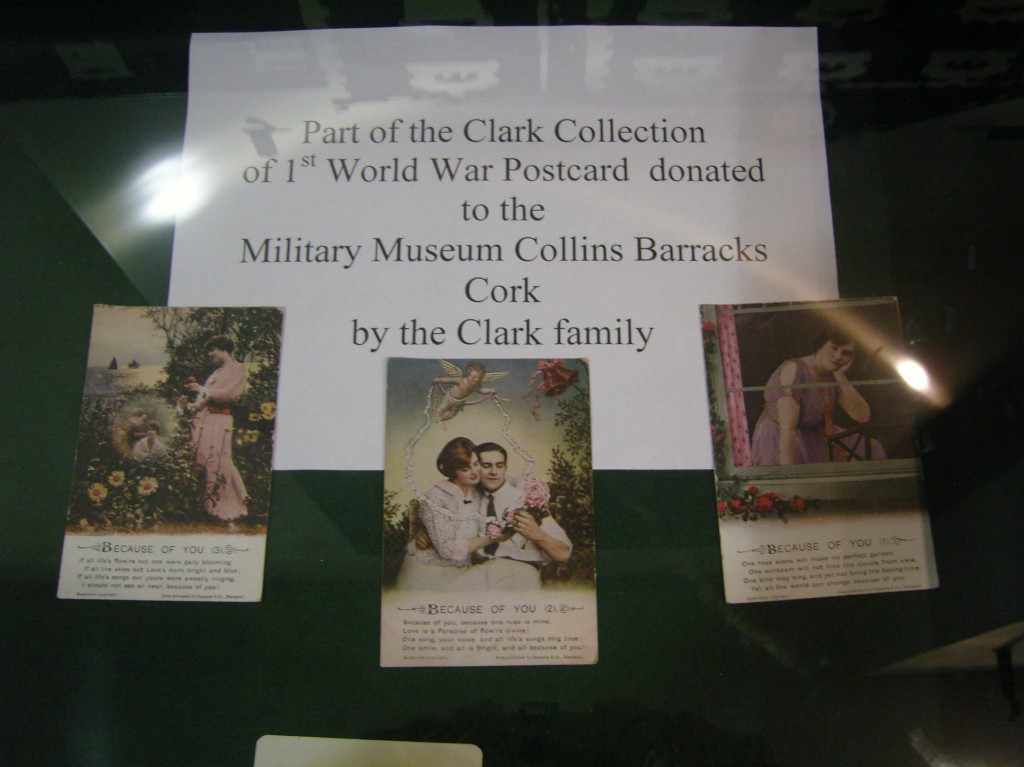

Cork barracks museum places more emphasis on the struggle for independence than Kilkenny, but this is to be expected as the complex is named after Michael Collins, Cork’s most revered son. There is a whole room dedicated to him. Located in the old Guard Room, the museum is palatial compared to Kilkenny and considerably better resourced. Scattered among the ‘fight for Irish freedom’ exhibits are a hints of other stories such as these World War I postcards.

Other exhibits range from the curious (a barracks bell replaced because a ‘bench of bishops’ was coming to visit) to the grand (British army regimental silver). I enjoyed learning about the lives of Irish soldiers who served in the barracks, playing sports and founding music societies. This museum has many exhibits and a wonderful view of the vast barrack square but reflections on whether the garrison affected civilian life are lost among the uniforms in display cases. Tying military and social history together may not appeal to military buffs but the case is unanswerable. A few hundred metres away from the gates of Cork Barracks, on Military Road, is Barrackton post office.

The barracks so throughly imposed itself on the geography and culture of this neighbourhood that there is no linguistic connection between the Irish-langauge placename, Gleann Ciotáin, and the English, Barrackton. 8 The barracks is a pervasive and profound presence in the landscape. A mention of this wouldn’t go astray in a tourist exhibition….

- H. R. Clarke, A New History of the Royal Hibernian Military School (2011) p. 85. ↩

- Having spoken to people who took tours with other operators, the same broad narratives are told by all. ↩

- http://www.spikeislandcork.com/island-purgatory Accessed 10 November 2012. ↩

- Peter Harte, The IRA and its Enemies: Violence and Community in Cork 1916-23 (Oxford, 1998) p. 112. ↩

- http://www.spikeislandcork.com/irish-prison-service-spike accessed 9 November 2012. ↩

- A standard hagiographical take on Republican prisoners on Spike Island can be seen in the TG4 documentary Ealú (Escape) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MtLH51t0uBE. Broadcast in 2010, http://www.iftn.ie/?act1=record&only=1&aid=73&rid=4282955&tpl=archnewshome&force=1 Accessed 9 November 2012. ↩

- http://www.corkcoco.ie/co/web//Cork%2520County%2520Council/Departments/Corporate%2520Affairs/Media%2520Releases?did=213891373 Accessed 12 November 2012. ↩

- ‘Gleann’ means Glen, ‘Ciotáin’ could be a variation on a number of words, from ‘ciota’ (wooden mug) to ‘ciotach’ (left-handed, awkward). To explore Irish and English placenames, see http://www.logainm.ie/ Accessed 13 November 2012. ↩